As March nears its end, ask yourself, how far have your readers come? Are you still wondering how to satiate your advanced readers? Do you still have readers who are “faking” it? Are students cringing through informational text with milk of magnesia-like reticence? Do some of your students still demonstrate significant deficits in vocabulary or background knowledge? The answer may lie in a dormant curiosity factor. Good readers press on to quench their curiosity about how octopuses squeeze through tiny spaces or how the villain will undermine her own conspiracy. So how do we address reader dispiritedness in the March doldrums? Productive curiosity is a potential solution. Teachers can hoist productive curiosity, or curiosity that bridges all of the cognitive gates, with focused, relevant analysis, inference, and synthesis orbiting around fascinating text. But how?

Using Text Sets to Drive Productive Curiosity

What is a text set?

A text set is a collection of high-quality texts organized around a specific topic. Text sets that drive productive curiosity orbit around unfamiliar topics of high interest. Consider yourself as a reader. Are you more likely to dive into a bin of books about making toast or a collection of texts unveiling the nine types of bacteria currently living around your toaster? We are curious about the unknown. We are productive when our effort feels relevant. Our students approach text in the same ways.

How are text sets constructed?

Text sets are constructed around an “anchor,” or complex grade-level text serving as the centerpiece for the curious and relevant topic in the unit. The anchor can be a full-length novel, an article, a primary source, a poem, or any piece of meaty text that necessitates other texts around it to grow related student background knowledge. The other texts in the set acts as a “staircase” building the background knowledge and vocabulary for students to actively engage with the anchor. The staircase also ensures that students move up and down the set through various complexity levels and text types to deepen, reinforce, and connect ongoing learning. The texts in a set “talk to one another” in that each stair is equally relevant.

What’s in a text set?

Texts in a set can include print, visual, auditory, and statistical formats. Varied text formats demand that students activate a multitude of cognitive processes and engage a variety of tools to hold on to knowledge and vocabulary. Notes, concept maps, rolling knowledge journals, vocabulary sorts, and text-dependent questions help students analyze text, capture critical ideas, and prepare to synthesize this new knowledge through meaningful tasks. Texts in a set might include a whole book (e.g., a novel, a picture book), excerpts from a lengthy text (e.g., a chapter, a section from a speech), short text (e.g., poems, articles, song lyrics, “juicy” sentences), photographs, videos, maps, charts, tables, graphs, primary sources, and/or models, among others.

What distinguishes strong and less effective text sets?

A text set is most effective if the topic is focused and specific (e.g., Life in the Pre-Civil Rights South) rather than broad and generic (e.g., Ancient Civilizations). The most effective topics are those that are curious to students (rather than the teacher!). Consider those topics with an “ick” factor (e.g., tongue-eating lice) or those that are provocative and intriguing (e.g., literary monsters). Novel topics offer high levels of curiosity, along with some cognitive discomfort, as they demand knowledge building and decision-making grounded in text rather than privileging or relying on existing experience. Productive curiosity is maximized when the whole class embarks on an uncharted topical journey together because:

- No students will “already be the experts”

- Students will need each other to see evolving and opposing points of view

- Students will endure the productive struggle of integrating new information together

- Reliance on the texts in the set become crucial (as opposed to reliance on prior knowledge gathered through privilege or experience)

Strong sets are comprised of high-quality primary source texts (e.g., constitutional amendment, speech, photograph, data collected from an experiment, an interview transcript or audio recording) and secondary source texts (e.g., news article, book, timeline, map, essay, song). Effective text sets include a balance of informational and literary texts, ideally with a 50-50 ratio of nonfiction to fiction texts in elementary grades and 70-30 nonfiction to fiction at middle and high school grades. Strong text sets spotlight literary nonfiction with informational text structure, such as opinion essays, biographies, journal articles, documentaries, and speeches, while also including narrative nonfiction with story-like structure (e.g., memoirs, diaries).

Highly Effective Text Sets

Build knowledge around a specific, unfamiliar topic (e.g., Pandemics, Harlem Renaissance, Freedom Fighters vs. Terrorists)

All texts ensure access to the anchor text and it’s embedded topic (e.g., texts in the set on racism and life in the pre-Civil Rights South build access for the anchor text To Kill a Mockingbird)

Texts include a variety of informational and literary selections, including primary sources (photographs, speeches, documentary video clips, etc.) and secondary sources (news articles, biographies, poems, picture books, a novel, etc.)

Texts span multiple genres and modalities (audio, visual, print, etc.)

Less Effective Text Sets

Engage students in exploration of a theme (e.g., friendship, courage, perseverance) or genre (e.g., poetry, historical fiction, mystery)

Texts are loosely related or unrelated to the anchor text and its central topic

Texts are mostly derived from contrived, highly-distilled sources (e.g., textbooks, abridged works, summaries of more complex text)

Texts are limited to one genre and include only traditional print formats

How does a text set support the range of readers in a classroom?

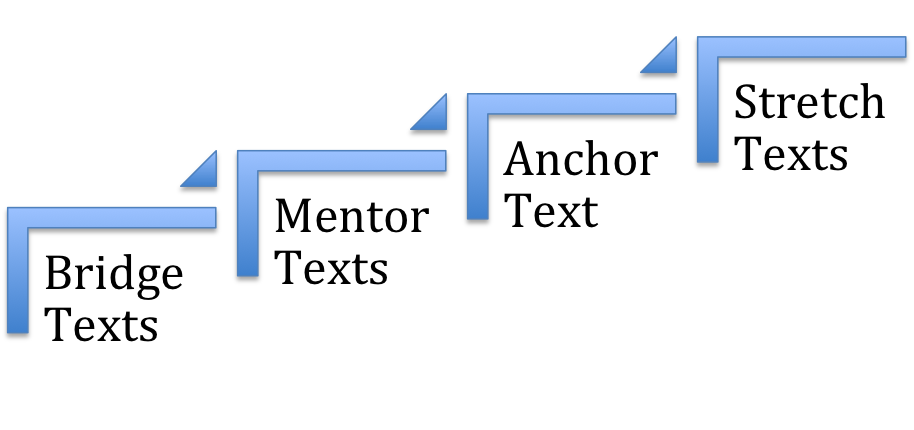

Common core standards demand that all students engage in analysis, inference, and synthesis of grade-level complex text. As a result, effective sets support purposeful access to meaty text. Strategic design of the text set “staircase” can ensure scaffolding without denying all readers the productive curiosity, and productive struggle, associated with complex text. The following continuum helps to ensure an appropriate staircase:

Bridge Texts

Bridge texts are topical texts in the set that are highly connected to the anchor and topic but at lower complexity levels than demanded at that grade. Bridge texts do not replace other texts in the set but are available to all students to serve as a “bridge” toward the anchor. Bridge texts fill a void of topical knowledge and vocabulary at more highly accessible text levels.

Mentor Texts

Mentor texts are moderately complex grade-level texts in the set that are tightly connected to specific content in the anchor and topic, but at mid-range quantitative and qualitative levels for the grade. Mentor texts are often excerpts (paragraphs, stanzas, chapters, pages, etc.) from more lengthy, demanding texts, thereby keeping rigor ambitious yet achievable. All students have access to mentor texts in the set.

Anchor Text

The anchor text is a richly complex grade-level text, pushing the upper quantitative and qualitative bands for the grade, that serves as the centerpiece for reading and unearthing the topic in the text set. The anchor necessitates reading across the set to amass the background knowledge, perspective, and vocabulary necessary to independently think, talk, and write about its central ideas.

Stretch Texts

Stretch texts that are selections in the set falling two to three grade levels above the grade, allowing advanced readers to dive deeper into the topic and acquire even more sophisticated vocabulary. Stretch texts are available to all students but do not contain crucial content for accessing the topic or anchor. Therefore, some students may decide not to access stretch texts in a set.

The continuum of texts in a set, from bridge to stretch, ensure that all students can become productively curious about the topic and the anchor text, while maintaining grade level rigor. But what about our students that are reading well below grade level? First, consider these three questions:

- Might these students want to attend a college of their choice?

- Do these students have a right to attend college without spending years in remedial courses?

- Will these students be taking state-wide standardized tests?

If you answered yes to any of these questions, then these students need regular access to the texts they will encounter in these instances. States with common-core aligned accountability measures will demand students read grade-level complex text. Colleges will demand that students read richly complex topical texts. Our choices around text need to be purposeful in ensuring that students have a chance to grapple with complex text in the safety of our classrooms. We won’t be there to help them in their college dorm at midnight, or even on the state test during fourth period.

Second, consider these three questions:

- Are these students ELLs with significant language needs?

- Are these students with highly specialized cognitive, physical, or social/emotional needs?

- Are these students who are reading many levels below their grade?

If you answered yes to any of these questions, you should include “supplemental” texts, along with the set, to support the unique needs of these students. Individual students may tap into these supplemental texts to overcome critical gaps in word-level and comprehension-level reading strategies and content knowledge. Supplemental texts may be bilingual resources, audiobooks, abridged versions, or “chunked” texts lifted from original sources, among others. While these supplemental texts may not be enough to leverage independent access to the text set for these students, they will increase opportunity for productive curiosity around the topic when texts in the set are read aloud by a teacher or peer and discussed. Shared reading of texts can take place in small groups with a teacher or with strategically partnered students who can demonstrate and support rich conversation and language models around the texts. Supplemental texts do not replace texts in a set, but make the topic far more accessible for students with specialized needs.

How can a text set be used before, during, and after instruction?

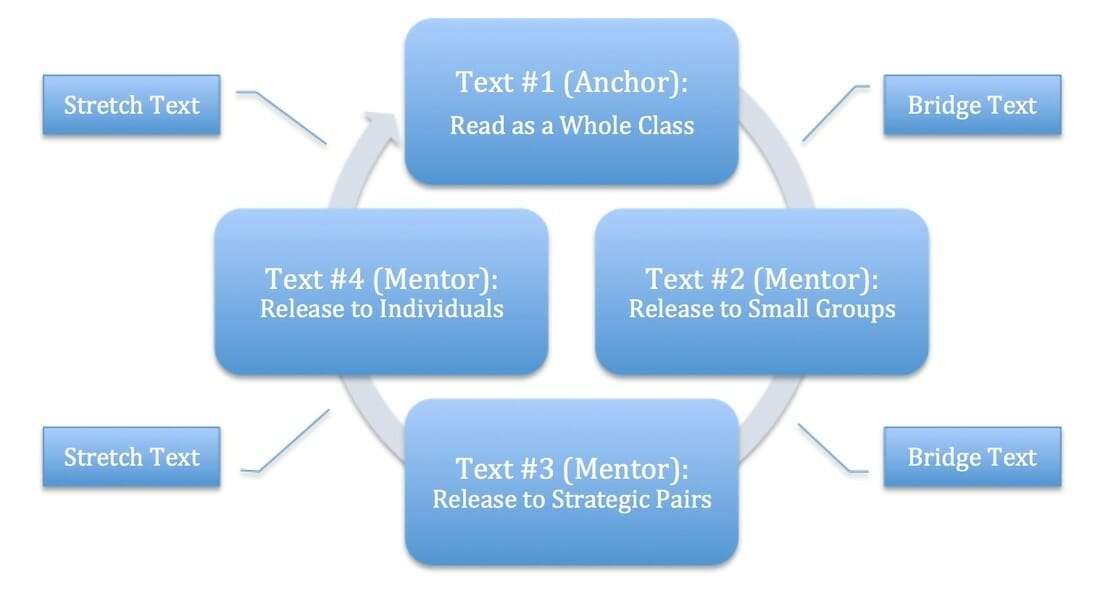

With so many texts in a set, gradual release and deliberate progression become essential. One approach to releasing students through a set involves the teacher using each text as a guidepost along the topical journey for students. Consider the following progression of gradual release through a complex text investigation:

Add as many mentors to the cycle as necessary. Insert bridge and stretch texts where appropriate and encourage students to self-select these texts based on their interest and need by asking questions like, “How can you find out more about that?” and “What unanswered questions do we have that might require additional texts to explore?”

Students can read bridge and stretch texts during independent reading, alongside of mentor texts, and for homework to debug or deepen topical knowledge. If you use and activator (or “do now”) to start your class, bridge texts and stretch texts can help students define key vocabulary using contextual clues or word-solving strategies. Additionally, bridge and stretch texts can be used during activators as “ten-minute fluency boosts” through which students can read the text chorally. Alternatively, support fluency by turning bridge texts into cloze reading passages. Eliminate every fifth word in a bridge text passage and have partners deliberate the missing words as they read aloud together. Strategically paired advanced readers could do this same cloze work with stretch texts.

The goal of the set is to continually return to the anchor with a deepening knowledge of the topic and a growing, authentic purpose for synthesizing the central ideas of the anchor. The more students read across the text set, the more they should care about the implications of the big ideas on their world.

How does productive curiosity and text-setting fit into Workshop 2.0?

Workshop structure allows productive curiosity to effectively blossom for all students. Here are some suggestions for maximizing the independence and joy inherent in workshop when using text sets:

- Explicitly model reading strategies in your mini-lessons as you move students through the text set. Don’t forget, one purpose of a text set is to drive productive curiosity so that students:

-

- Develop stamina for reading

- Build intrinsic motivation to read increasingly complex text (because they NEED to know more about this juicy topic!)

- Read for an authentic purpose

None of this is possible without effective reading strategies. As you plan your mini-lessons, ask yourself, “What strategy am I teaching my readers today that they haven’t already mastered?” and “How will today’s texts allow them to practice this strategy with increasing independence?”

- Integrate teacher-created text sets with special topical collections you spotlight in your classroom library. Allow students to grow your teacher-created set by adding student-selected bridge, mentor, and stretch texts from your library (or the school library if you don’t have a classroom library).

- Create DIY stations that allow students to construct their own text sets on the topic. Photocopy and/or gather all possible texts for a set but do not pre-construct the collections for students. Sort them into categories that help students recognize which are critical readings for the topic. Category labels might include “must-know” ideas, “great-to-know” ideas, and “nice-to-know” ideas. Have students conduct a “book pass” or “text pass” to skim and scan the selections and build their own group-selected set by choosing two texts from each category. Of course, students can always add additional pieces from your categories over the course of the unit if they need more support or enrichment. Group-created text sets cause interesting variations in the knowledge and point-of-view base across the class, driving productively curious conversation.

- Use conferring opportunities to assess and intervene as students grapple with the various complexity levels in the set. Research one strength the reader demonstrates in the conference, along with one critical strategy you can model to help the reader improve comprehension. Provide a chance for the student to practice this strategy with fidelity before moving on to your next conference.

- Add new texts that offer scaffolding, specific features, or incremental rigor for small groups in which you provide explicit instruction. These texts may be matched to the instructional reading level of students in the group, in the case of guided reading, or represent multiple reading levels, in the case of strategy groups.

- Ask students to continually add their own personally selected texts to the set. These texts can serve as stretch or bridge texts (independent or “just-right” texts at the students individual reading level) or mentor texts that become integral to the topical study. Help students make meaningful selections by modeling ways in which you find and integrate new texts into the set as a reader (e.g., finding an article on the dung beetle to deepen your text set on insect adaptations). Model for students how adding your own text greatly enhances your productive curiosity.